MOST READ

- Cindytalk - Sunset and Forever | シンディトーク

- Visible Cloaks ──ヴィジブル・クロークスがニュー・アルバムをリリース

- interview with Autechre 来日したオウテカ──カラオケと日本、ハイパーポップとリイシュー作品、AI等々について話す

- Fumitake Tamura ──「微塵な音」を集めたアルバム『Mijin』を〈Leaving Records〉より発表

- SUGAI KEN ──3月に欧州ツアー、チューリッヒ、プラハ、イスタンブール、ローマ、アントワープの5都市を巡回

- ele-king presents HIP HOP 2025-26

- 別冊ele-king 坂本慎太郎の世界

- HELP(2) ──戦地の子どもたちを支援するチャリティ・アルバムにそうそうたる音楽家たちが集結

- KEIHIN - Chaos and Order

- DADDY G(MASSIVE ATTACK) & DON LETTS ——パンキー・レゲエ・パーティのレジェンド、ドン・レッツとマッシヴ・アタックのダディ・Gが揃って来日ツアー

- 坂本慎太郎 - ヤッホー

- Geese - Getting Killed | ギース

- Thundercat ──サンダーキャットがニュー・アルバムをリリース、来日公演も決定

- CoH & Wladimir Schall - COVERS | コー、ウラジミール・シャール

- Shintaro Sakamoto ——坂本慎太郎LIVE2026 “Yoo-hoo” ツアー決定!

- The Master Musicians of Joujouka - Live in Paris

- IO ──ファースト・アルバム『Soul Long』10周年新装版が登場

- interview with Shinichiro Watanabe カマシ・ワシントン、ボノボ、フローティング・ポインツに声をかけた理由

- Reggae Bloodlines ——ルーツ時代のジャマイカ/レゲエを捉えた歴史的な写真展、入場無料で開催

- Columns 1月のジャズ Jazz in January 2026

Home > Reviews > Album Reviews > HAINO KEIJI & THE HARDY ROCKS- きみはぼくの めの「前」にいるのか すぐ「隣」にいるのか

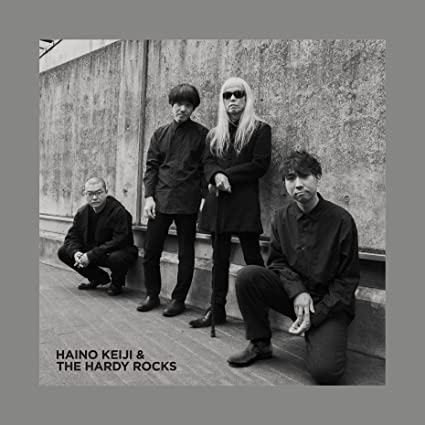

HAINO KEIJI & THE HARDY ROCKS

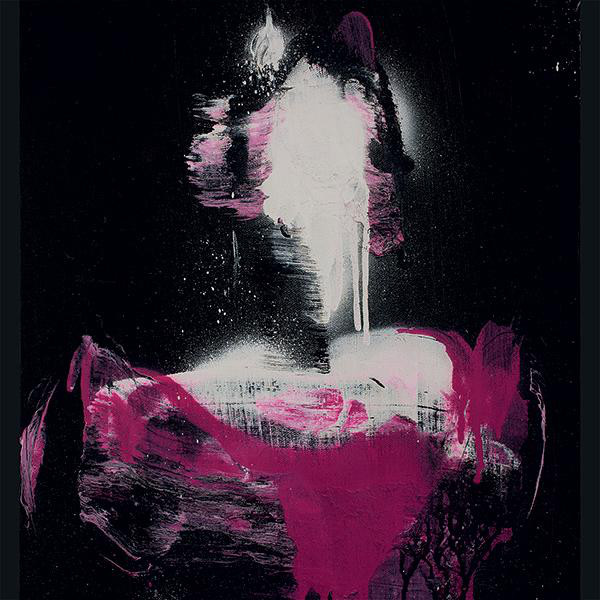

きみはぼくの めの「前」にいるのか すぐ「隣」にいるのか

“You’re either standing facing me or next to me”

Pヴァイン

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド、松山晋也(訳:江口理恵) Aug 19,2022 UP

文:ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド(訳:江口理恵)[8月19日公開]

1960年代に入ってしばらくするまで、カヴァー・ヴァージョンというのはロック・バンドが普通にやるものだった。ビートルズの最初の2枚のアルバムに収録されている曲の半分近くは他のアーティストの作品だ。初期のローリング・ストーンズは、自らのソングライターとしての才能を証明するよりも、ボ・ディドリーを模倣することの方に関心があった。しかし、LPがロック・ミュージックのフォーマットに選ばれるようになると、ファンはアーティストにより多くの革新を期待し、レーベルもオリジナルの音源の方が金になることに気付き出した。カヴァー・ヴァージョンは、ありふれたお馴染みのものから、ロック・ミュージシャンがより慎重に意図を持って使うものになっていった。敬意を表したり、いつもの定番曲に新風を吹き込んだり、キュレーターとしてのテイストをひけらかしたり、あるいは完全に冒涜的な行為を行うための。

『きみはぼくの めの「前」にいるのか すぐ「隣」にいるのか』の収録曲では、これらのことの多くが、時に同時進行で行われている。灰野敬二が70歳の誕生日を迎えたわずか数週間後にCDとしてリリースされたこの変形したロックのカヴァー集は、実質的にはパーティ・アルバムであり、クリエイターの音楽的ルーツを探る、疑いようのない無礼講なツアーのようだ。全曲を英語のみで歌う灰野敬二が、角のあるガレージ・ロック・スタイルのコンボ(川口雅巳(ギター)、なるけしんご(ベース)、片野利彦(ドラム))のヴォーカルを務め、ロックの正典ともいうべき有名曲のいくつかを、ようやくそれと認識できるぐらいのヴァージョンで披露している。

灰野がカヴァー・バンドのフロントを務めるというのはそれほどばかげた考えではない。彼の1990年代のグループ、哀秘謡では、ドラマーの高橋幾郎、ベースの川口とともに、50年代・60年代のラジオのヒット曲の、幻覚的な解釈をしてみせた。ザ・ハーディ・ロックスの前には、よりリズム&ブルースに焦点を当てたハーディ・ソウルがあり、その一方で灰野はクラシック・ロックの歌詞を即興のライブ・セットに取り入れることでも知られていた。つまり、このアルバムが、一部の人間が勘違いしそうな、使い捨てのノヴェルティのレコード(さらに悪くいえば、セルフ・パロディのような行為)ではないことを意味している。

2017年に、ザ・ハーディ・ロックスを結成したばかりの灰野にインタヴューしたとき、彼はバンドがやっていることを「異化」という言葉で表現した。これは英語では“dissimilation”あるいは“catabolism”と訳されるが、ベルトルト・ブレヒトの、観客が認識していると思われるものから距離を置くプロセスである“Verfremdung”の概念にも相当する。ここでは“(I Can’t Get No ) Satisfaction”のように馴染み深い曲でさえ、じつに奇怪にきこえる。キース・リチャーズの3音のギター・フックが重たいドゥームメタル・リフへと変わり、灰野が喉からひとつひとつの言葉をひねり出すような激しさで歌詞を紡ぐ。驚くべきヴォーカル・パフォーマンスを中心にして音楽がそのまわりを伸縮し、次の“Hey Hey Hey”への期待で、いろいろな箇所で震えて停止してしまう。

あえて言うまでもないが、灰野は中途半端なことはしない。レコーディング・エンジニアの近藤祥昭が、不規則で不完全な状態を捉えたこのアルバムでの灰野のヴォーカルは、まるで憑りつかれているかのようだ。金切り声や唾を吐く音が多いにもかかわらず、何を歌っているのか判別するのはそれほど難しいことではない。バンドは重々しい足取りでボブ・ディランの“Blowin’ In The Wind”をとりあげているが、それはもっとも不機嫌な不失者のようでオリジナルとは似ても似つかないが、それでもディラン自身が2018年のフジロックフェスティバルで演奏したヴァージョンよりは曲を認識できる。

注意深く聴くとたまに元のリフが無傷で残っているのがわかるが、音の多くの素材は、不協和音のコード進行や故意に不格好なリズムで再構築されている。このバンドの“Born To Be Wild”では、有名なリフレインに辿り着く前に灰野がジョン・レノンの“Imagine”からこっそりと数行滑り込ませている。“My Generation”では、崩壊寸前の狂気じみた変拍子でヴァースに突進していく。川口が灰野のヴォーカルに合わせて支えるように、しばしば、エフェクターなしでアンプに直接つないだ生々しいギターの音色を響かせる。なるけと片野は、様々なポイントでタール抗の中をかき分けて進むかのように演奏している。

ビッグネームのカヴァーが多くの人の注目を引くだろうが、ザ・ハーディ・ロックスは、日本のMORでも粋なことをしている。アルバムのオープニング曲の“Down To The Bones”は、てっきり『Nuggets』のコンピレーションの収録曲を元にしていると思っていたが、YouTubeのプレイリストを見て、これが実際には1966年に「骨まで愛して」で再デビューした歌謡曲のクルーナー、城卓矢のカヴァーだと判明した。“Black Petal”は、水原弘の“黒い花びら”をプロト・パンク風の暴力に変えるが、日系アメリカ人デュオのKとブルンネンの“何故に二人はここに”については、灰野にかかっても救いようのない凡庸さだ。

もっとも異彩を放つのは、アルバム終盤に収録されたアカペラ・ヴァージョンの“Strange Fruit”だろう。これは奇妙な選択であり、「Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze(黒い体が南部の風に揺れる)」という歌詞を静かに泣くように歌い、本当の恐怖を伝える灰野の曲へのアプローチの仕方には敬意を表するが、私はこの曲を再び急いで聴こうという気にはならない。しかし、アルバム全体は非常に面白く、このクリエイターの近寄り難いほど膨大なディスコグラフィへの入り口としては、理想的な作品である。

HAINO KEIJI & THE HARDY ROCKS

きみはぼくの めの「前」にいるのか すぐ「隣」にいるのか

(“You’re either standing facing me or next to me”)

P-Vine Records

by James Hadfield

Until well into the 1960s, cover versions were just something that rock bands did. Nearly half of the songs on the first two Beatles albums were by other artists. The early Rolling Stones were more interested in channeling Bo Diddley than in proving their own abilities as songwriters. But as the LP became the format of choice for rock music, fans began to expect more innovation from artists, while labels came to realise there was more money to be made from original material. Cover versions went from being ubiquitous to something that rock musicians used more sparingly, and intentionally: to pay respects, put a fresh spin on familiar staples, flaunt their curatorial taste, or commit acts of outright sacrilege.

The songs on “You’re either standing facing me or next to me” are many of these things, sometimes all at once. Released on CD just a few weeks after Keiji Haino celebrated his 70th birthday, this collection of deformed rock covers is practically a party album, and a distinctly un-reverential tour of its creator’s musical roots. Singing entirely in English, Haino acts as vocalist for an angular, garage rock-style combo (consisting of guitarist Masami Kawaguchi, bassist Shingo Naruke and drummer Toshihiko Katano), who serve up just-about-recognisable versions of some of the most famous entries in the rock canon.

The idea of Haino fronting a covers band isn’t as absurd as it may seem. His 1990s group Aihiyo, with drummer Ikuro Takahashi and Kawaguchi on bass, did strung-out interpretations of radio hits from the ’50s and ’60s. The Hardy Rocks were preceded by the more rhythm and blues-focused Hardy Soul, while Haino has also been known to incorporate lyrics from classic rock songs into his improvised live sets. All of which is a way of saying that this isn’t the throwaway novelty record that some might mistake it for (or, worse, an act of self-parody).

When I interviewed Haino in 2017, not long after he’d formed The Hardy Rocks, he used the term “ika” (異化) to describe what the band were doing. The word can be translated as “dissimilation” or “catabolism” in English, though it also corresponds with Bertolt Brecht’s idea of “Verfremdung”: the process of distancing an audience from something they think they recognise. Even a song as familiar as “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” sounds downright freaky here. Keith Richards’ three-note guitar hook is transformed into a lumbering doom metal riff, as Haino delivers the lyrics with an intensity that suggests he’s wrenching each word from his own throat. It’s a remarkable vocal performance, and the music seems to expand and contract around it, at various points shuddering to a halt in anticipation of his next “Hey hey HEY.”

As if it needed stating at this point, Haino doesn’t do anything by halves, and his vocals on the album—captured in all their ragged imperfection by recording engineer Yoshiaki Kondo—sound like a man possessed. But for all the shrieks and spittle, it’s seldom too hard to figure out what he’s actually singing. The band’s lumbering take on Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind”—like Fushitsusha at their most morose—may sound nothing like the original, but it’s still more recognisable than the version Dylan himself played at Fuji Rock Festival in 2018.

Listen closely and you can pick out the occasional riff that’s survived intact, though more often the source material is reconfigured with dissonant chord sequences and deliberately ungainly rhythms. The band’s version of “Born To Be Wild” eventually gets to the song’s famous refrain, but not before Haino has slipped in a few lines from John Lennon’s “Imagine.” On “My Generation,” they hurtle through the song’s verses in a frantic, irregular meter that’s constantly on the verge of collapse. Kawaguchi matches Haino’s vocals with a bracingly raw guitar tone, often jacking straight into the amp without any effects pedals. At various points, Naruke and Katano play like they’re wading through a tar pit.

While it’s the big-name covers that will grab most people’s attention, The Hardy Rocks also do some nifty things with Japanese MOR. I was convinced that album opener “Down To The Bones” was based on something from the “Nuggets” compilations, until a YouTube playlist alerted me to the fact that it was actually “Hone Made Ai Shite,” the 1966 debut by kayōkyoku crooner Takuya Jo. “Black Petal” turns Hiroshi Mizuhara’s “Kuroi Hanabira” into a bracing proto-punk assault, though the band’s take on “Naze ni Futari wa Koko ni,” by Japanese-American duo K & Brunnen , is a pedestrian chug that even Haino can’t salvage.

The most out-of-character moment comes near the end of the album, with an a cappella version of “Strange Fruit.” It’s an odd choice, and while I can respect the way that Haino approaches the song—delivering the lyrics in a hushed whimper that conveys the true horror of those “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze”—it isn’t a track that I’ll be returning to in any hurry. But the album as a whole is a hoot, and an ideal entry point into its creator’s intimidatingly vast discography.

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド

ALBUM REVIEWS

- Cindytalk - Sunset and Forever

- CoH & Wladimir Schall - COVERS

- KEIHIN - Chaos and Order

- DIIV - Boiled Alive (Live)

- 坂本慎太郎 - ヤッホー

- aus - Eau

- 見汐麻衣 - Turn Around

- Taylor Deupree & Zimoun - Wind Dynamic Organ, Deviations

- Ikonika - SAD

- Eris Drew - DJ-Kicks

- Jay Electronica - A Written Testimony: Leaflets / A Written Testimony: Power at the Rate of My Dreams / A Written Testimony: Mars, the Inhabited Planet

- DJ Narciso - Dentro De Mim

- The Bug vs Ghost Dubs - Implosion

- Debit - Desaceleradas

- Sorry - COSPLAY

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE