MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

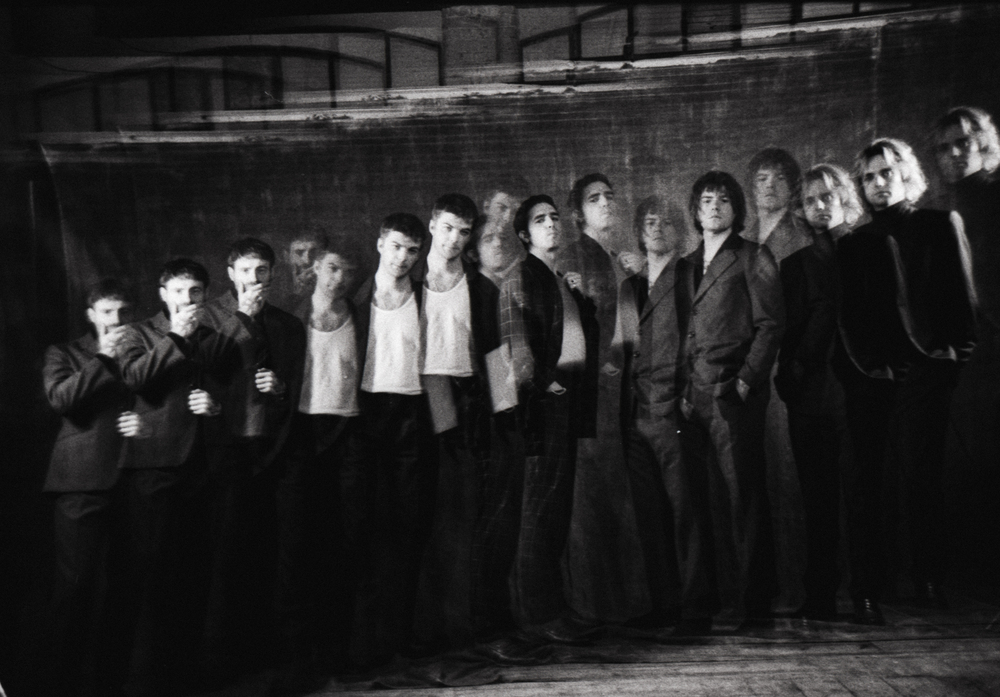

Home > Reviews > Album Reviews > Fontaines D.C.- Skinty Fia

故郷であるイギリスの地元の街のことで度々蘇る記憶のひとつに、パークストリートの頭上を覆うように堂々とそびえ建つバロック建築のブリストル博物館がある。陰鬱な古い絵画、ブリストルの航空史を記念する品の数々、征服者のローマ人が遺した異国の古代の遺物、あるいはイギリス自身が植民地で略奪した遺物とともに、アイリッシュエルク、またはジャイアント・アイリッシュ・ディア(ギガンテウスオオツノジカ)として知られる、絶滅して久しい生物の巨大なスケルトンが展示されている。

このグロテスクで威厳のある、恐ろしいほど巨大な鹿の骸骨と、異様なほど脆そうに見える脚は、ブリストルの子供たちの悪夢に度々現れる。この標本自体はイングランド南西部で発掘されたと思われるが(アイリッシュエルクは当時ヨーロッパとロシアの間を広くうろついていた)、この種とアイルランドとの結びつきには、馴染み深いものと、どこか異質なものの両側面が存在する。

ウェールズ人の母とアイルランド人の父の息子であるイギリス人の私にとって、馴染み深いものと異質なものとの衝突は、自分自身の中の遺産の断片が、どのように組み合わされているのかを探って理解しようと試みる時に必ずついてまわるものだ。イングランドに生まれながら、アイルランドの血も入った自分にとってあの堂々たる骸骨は、自分自身の、置き去りにした部分からの告発であり、霊的な記憶のようでもある。

アイリッシュエルクの絶滅が題材となっているアイルランド語の呪文“Skinty Fia(スキンティ・フィア)”は、“鹿の天罰”と訳され、この言葉をアルバム・タイトルに採用したアイルランド出身のバンド、フォンテインズD.C.は、 故郷(バンド名のD.C.はダブリン市の意)を離れてロンドンに向かう過程で、彼らのなかのアイルランド人らしい感覚がどう変わったかという葛藤を探る方法として活用している。彼らはインタヴューのなかで、たびたびこれを自分の存在が血統に左右されるという意味においての“悲運”のテーマだと説明しており、そのもっとも露骨な方法のひとつがアイルランド人らしい、あからさまなサインをイギリス人がどう解釈するかだと述べているのだ。

アルバムのオープニング・ソングでは、アイルランド語の「In ár gCroíthe go deo(永遠に私たちの心のなかに)」という害の無いフレーズを引用しているが、これはアイルランド生まれの女性、マーガレット・キーンの遺族が、彼女の死後、墓石にこの言葉を原語のまま、英語への翻訳なしで使用することを英国国教会が禁じて、イギリスで論争の的となった言葉だ。教会側の言い分としては、イングランドでは、アイルランド語が政治的な意味合いを持つものに見られる可能性があるということを理由にあげた。この可能性というものこそが、イングランドにおけるアイルランドへの広範にわたる不快感を露呈している。何世紀にもわたって征服し、植民地化し、飢えさせ、薄切りにして切り離した国に対する彼ら(僕ら?)イギリス人の植民地に対する不安のパンドラの箱を開ける楔なのである。

20世紀後半の大半にわたって、イギリス人が抱くアイルランド人のイメージは、北アイルランド(現在もUKの一部)に駐留するイギリスに対抗する派閥の、戦う“アイリッシュ・テロリズム”であった。私が生まれた数ヶ月後に、ブリストルにあるアイリッシュエルクの骸骨標本が佇む博物館から僅か数メートル離れた先で、IRAの爆弾が爆発し、自分の幼少期には爆発の警告が日常茶飯事だった。

一方で、アイルランド人はしばしば、愚かで酒飲みの野暮ったい“パディ”として、ジョークの的にされることも多かった。これらふたつのアイルランドらしさを表すとされた存在感は、イギリス人の発想の中で密接に結びついており、ジョークで、自分たちが彼らの国にしたことへの罪悪感を和らげ、いまだに存在する、私たちに向けられる怒りを弱めようとした。スコットランド人であるアズテック・カメラと、ウェールズとロシア系ユダヤ人の両親を持つイギリス人のミック・ジョーンズが“Good Morning Britain”という曲で歌ったように、「Paddy’s just a figure of fun / It lightens up the danger (パディはただの遊び道具 / 危険を軽減してくれる)」のだった。

しかし、『Skinty Fia』は、単純に差別に対する非難というわけではない。歌詞には直接的な表現はほとんどなく、しばしば抽象的あるいは隠喩的なやり方でイギリスと自分たちのかつての故郷の両方に対するバンドの関係性の感覚を、より複雑な層にまで探究する。アイルランド国内においても、首都ダブリンとアイルランド語を話すような田舎のエリアとでは違いが存在する。英語の“beyond the Pale(境界を越えて、常軌を逸した)”という表現は、こうした地方のことを指し、許容範囲や文明的な限度を超えた行動という慣用句としての意味を持つフレーズだ。

一方、地方出身者は、ダブリン出身者を“Jackeens(ジャッキーンズ)”と呼び、イギリス化した「リトル・イングリッシュ」と表現することがある(パトリック/パディはアイルランド人に多い名前であり、英国旗が“ユニオン・ジャック”と呼ばれるように、ジャックはイギリス人に多い名前)。フォンテインズD.C.は、“Jackie Down the Line”でこの表現をほのめかし、自分たちの言葉として使っているが、これはイギリスが自分たちを変えようとしていることを敏感に感じ取っているからかもしれない。

アルバムに通底しているのは、変化と、変わらないこととの間に流れる緊張感であり、バンドはほとんどアイルランドらしさを失うことなく、イギリスでもアイルランドでもない、等しい価値のある、新しい何かに変異させるべく表現している。“Roman Holiday”では、アウトサイダーとしての自分たちの立場に誇りを感じて喜び、冒険のように“ロンドンを受け入れる”ことを歌った曲だと説明している──彼らはおそらく、自分たちの異質性を受け入れると同時に、今では彼ら自身がその小さな一端となっているアイルランドのディアスポラ(離散)も、ある程度受け入れているのだろう。

フォンテインズD.C.自身もそうであるように、アイルランドのディアスポラの一部は、野心家のアーティストたちが観客とクリエイティヴな仕事の機会を求めて旅した結果でもあった。ダブリナーだったマイ・ブラッディ・ヴァレンタインは故郷を離れ、マイクロディズニーのショーン・オヘイガン、ハイ・ラマズとステレオラブもコークを後にし、同様の旅に出た。“Big Shot”では、アーティストとしての名声と成功が気まぐれに約束されている大都市への移動の、何がリアルで、何が表面的なものに過ぎないのかがわからない不安を浮き彫りにしている。それに対して“Bloomsday”では、毎年6月16日に行われるジェイムズ・ジョイスの名高い小説『ユリシーズ』にちなんだダブリンの芸術史の祝いを呼び起こしている──これは特定の場所から生まれ、その場所の基礎構造の一部となるような創造的な作品なのかもしれない。どうやらフォンテインズD.C.が求めているのは、石や鉄骨や舗装された場所ではなく、一連の繋がりや記憶や物語に支えられた新しい居場所なのかもしれない。

自分自身にまつわる感覚的なものの多くを、博物館に展示された先史時代の鹿のスケルトンの細い脚のようなものに投影するのは、脆くて妖しいことと思われるかもしれないが、いわゆるブリティッシュ・ミュージックの歴史と成長に目を向けると、その血管にはアイルランドの血が流れていることがわかる。アイルランドから移動してきたアーティストに加えて、アイルランドのルーツはすでに存在し、非常に多くのものの礎となっている。ザ・ポーグスはロンドンのアイリッシュ・ディアスポラのど真ん中から誕生したし、ジョン・ライドン、ケイト・ブッシュ、ザ・スミス、ケヴィン・ローランド、ノエル&リアム・ギャラガー、ポール・マッカートニー、そして、やや遠縁にはジョン・レノンなどが、皆アイルランドのバックグラウンドを持っている。

しかし、私たちは“スキンティ・フィア”が、もともとは呪文であり、憤りや怒りの表現であることを忘れてはならない。あらゆる人間関係と同様に、このアルバムが描く変異のプロセスは、決してスムーズでも、快適でもないものだ。バンドが、自分たちのイギリスとアイルランドとの関係性を探る上で繰り返し立ち戻る隠喩が、有毒で機能不全のロマンスであることがそれを物語っている。彼らはアウトサイダーとしてロンドンを受け入れ、アイルランドに「I Love You」と、たびたび露骨で批判的な表現で歌うが、自分たちの過去に運命づけられている以上、そこからまた新しい何かを築き上げる望みはあるのだ。

Ian F. Martin

One of my abiding memories of my hometown in the UK is the imposing, baroque structure of Bristol Museum looming over the top of Park Street. Among the exhibits, taking in gloomy old paintings, mementos of Bristol’s aviation history, and ancient relics from overseas left behind by conquering Romans or looted during Britain’s own colonial adventures, there stands the towering skeleton of a long-extinct creature known as the Irish elk or giant Irish deer.

This grotesque, majestic, fearsomely huge skeletal deer with its strangely fragile looking legs haunts the nightmares of Bristolian children. And despite this particular specimen most likely having been unearthed locally in the southwest of England (the Irish elk roamed much of Europe and Russia in its day), there was something both familiar and alien about the species’ association with Ireland.

For me, the English son of a Welsh mother and an Irish father, that collision between the familiar and the alien is a constant feature of the way I try to understand how the fragments of my own heritage piece together. Born in England but somehow still of Ireland, that imposing skeleton is like a spectral memento or accusation from an abandoned part of myself.

The extinction of the Irish elk is the subject of the Irish language curse “skinty fia”, often translated as “the damnation of the deer”, and in taking it for the title of their new album, Irish band Fontaines D.C. have used it as a way of exploring the tensions in how their own sense of Irishness has changed in the process of leaving their home (the D.C. in their name refers to Dublin City) for London. In interviews they have often described it as a theme of “doom”, in the sense of one’s existence being in thrall to your lineage, and one of the most obvious ways that can manifest itself is in how English eyes interpret overt signs of Irishness.

The album’s opening song references the Irish phrase, “In ár gCroíthe go deo” — an innocuous phrase meaning “in our hearts forever”, which became the centre of a controversy in England when the bereaved family of an Irish-born woman named Margaret Keane were forbidden by the Church of England to use the words without a translation on Keane’s headstone. The church’s reasoning was that the Irish language might be seen by some in England as having political connotations, but that potential for discomfort reveals a broader discomfort within England towards Ireland. The alienness of the Irish language is the wedge that opens up a Pandora’s box of colonial anxieties the English have towards a country they (we?) have over the centuries conquered, colonised, starved and then sliced apart.

For much of the late 20th century, the main image of Irishness that English people had was of “Irish terrorism” from factions fighting against the ongoing British presence in Northern Ireland (which remains part of the UK). A few months after I was born, an IRA bomb exploded just a few metres up the road from the museum in Bristol where the Irish elk skeleton lurks, and bomb warnings were a regular feature of life growing up. The flipside of that was that Irish people were often the butt of jokes that portrayed them as foolish, drunk and unsophisticated “Paddies”. These two presences of Irishness in the English mindset went hand in hand, the jokes softening the English guilt for what we’d done to their country and diminishing the anger against us that still existed. As Aztec Camera (Scottish) and Mick Jones (English of Welsh and Russian Jewish parentage) sang in their song “Good Morning Britain”, “Paddy’s just a figure of fun / It lightens up the danger”.

“Skinty Fia” isn’t simply a tirade against discrimination, though. Rarely direct in its lyrics, it explores more complex layers of the band’s sense of relationship with both England and their former home in often abstract or metaphorical ways. Within Ireland itself, there are differences between the metropolitan seat of government in Dublin and the more rural, more Irish-speaking areas beyond. The English term “beyond the Pale” refers to those rural regions, the phrase carrying the idiomatic meaning of behaviour that goes beyond acceptable or civilised limits. Meanwhile, people from rural regions sometimes refer to Dubliners as “Jackeens”, painting them as Anglicised “little English” (just as Patrick/Paddy is a popular Irish name, Jack is a common English name, while the British flag is known as the Union Jack). On “Jackie Down the Line” Fontaines D.C. allude to this term and adopt it for themselves, perhaps touching on their sense of how England is changing them.

That sense of tension between change and holding on runs through the album, with the band describing it as not so much losing Irishness as mutating it into something neither English nor Irish, but new and equally valid. They have described “Roman Holiday” as a song partly about “embracing London” as an adventure, happy and proud in their status as outsiders — perhaps in a way embracing their own alienness, but also embracing the Irish diaspora of which they are now one small part.

As with Fontaines D.C. themselves, part of that Irish diaspora has been a result of ambitious artistic types travelling to where the audience and creative opportunities are. My Bloody Valentine were displaced Dubliners, while Sean O’Hagan of Microdisney, the High Llamas and Stereolab took a similar journey from Cork. It’s this move to the big city with its capricious promise of artistic fame and success that underscores the anxieties expressed about what is real and what superficial in “Big Shot”. In some ways, a counterpoint might be the way “Bloomsday” calls back to the storied artistic history of Dublin in its reference to the city’s annual June 16th celebrations of James Joyce’s novel “Ulysses” — a creative work born from a specific place that then itself becomes part of the fabric of that place. What Fontaines D.C. seem to be looking for is a new place to belong, anchored not in the stones, steel beams and tarmac of a place but in a series of links, memories and stories.

It may seem a fragile and spectral thing on which to carry so much of one’s sense of self, like the slender bone legs of a prehistoric deer skeleton in a museum, but one look at the history and growth of so-called British music reveals Irish blood running through its veins. In addition to those artists who travelled over from Ireland, already-existing Irish roots are fundamental to so much more. The Pogues were born right out of the heart of the London Irish diaspora, while John Lydon, Kate Bush, The Smiths, Kevin Rowland, Noel and Liam Gallagher, Paul McCartney and more distantly John Lennon all have Irish backgrounds.

We should remember, though, that “skinty fia” is originally a curse — an expression of exasperation or anger. And like any relationship, the process of mutation the album describes is not a smooth or comfortable one. It’s telling that one metaphor the band keep returning to in exploring their relationships with both England and Ireland is that of a toxic or dysfunctional romance. They embrace London as outsiders, they sing “I Love You” to Ireland couched in often explicitly critical terms, but for all that they are doomed by their past, there is some hope of something new to be built from it.

イアン・F・マーティン

ALBUM REVIEWS

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head/ Loula Yorke - Volta

- Actress - Statik

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant

- High Llamas - Hey Panda

- The Stalin - Fish Inn - 40th Anniversary Edition -

- KRM & KMRU - Disconnect

- Cornelius - Ethereal Essence

- Kronos Quartet & Friends Meet Sun Ra - Outer Spaceways Incorporated

- Martha Skye Murphy - Um

- Mouchoir Étanche - Le Jazz Homme

- Taylor Deupree - Sti.ll

- John Cale - POPtical Illusion

- Amen Dunes - Death Jokes

- A. G. Cook - Britpop

- James Hoff - Shadows Lifted from Invisible Hands

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE