MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

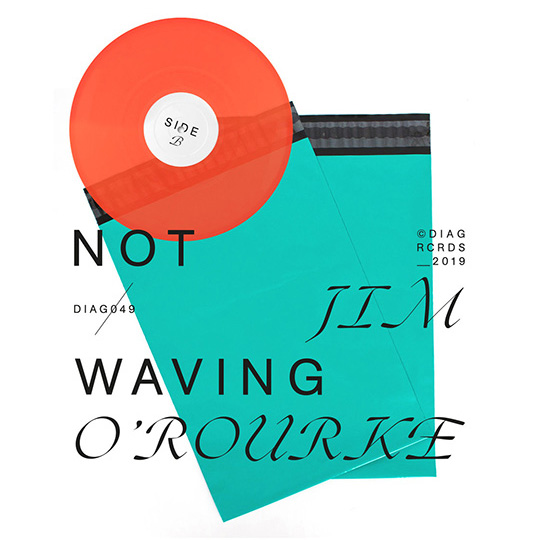

Home > Interviews > interview with Jim O’Rourke - "I don’t make music ‘cause I enjoy it"

interview with Jim O’Rourke

"I don’t make music ‘cause I enjoy it"

──an interview with Jim O'Rourke

Well, in terms of structure, the one thing that music can’t really do eloquently, like the other art forms, is deal with time backwards. Music can really only change time by making reference, and that can only be done if the music has a formal structure because you’re making structural reference or a melodic reference.

I:

So silence can be a function of the overall rhythm of the piece.

J:

Right, yes, exactly, yeah. Another thing I had to think about a lot when making this record is the idea that just because the music is “ambient” and doesn’t have percussion elements or whatever, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a rhythm. So, what role does rhythm take in this and how does it manifest itself is also something I had to think about a lot. And silence is part of that. Silence is kind of like an audio punctuation as well and it can be a comma or it can be a period. Or a semi-colon. Of course it matters what comes before and what comes after, but you really can hear the difference between a period and a comma. There’s definitely a moment of silence on this record that’s a comma and then there’s one that’s 3 periods in a row. At least that’s the way I think of it.

I:

Did you find, while making this record that there are cliches in ambient music?

J:

Oh, there definitely are. I kind of knew them before I started this because that’s mostly the reason I don’t listen to ambient music. I mean, pretty much all ambient music is major 7th chords, so harmony was going to be a big deal – how to approach harmony with this. Major 9th is also very popular: those are the two go-to harmonies in ambient music, if it isn’t just a perfect 5th. How to deal with harmony on this! I didn’t want it to just be about the overtones, because with the drone route really you’re dealing with overtones and not dealing with harmony – that was something I knew firsthand from doing it. In my memory, all the failed versions are sort of mixed up in it. Once I’ve finished the record, the only time I’ve heard it since mixing it is to check the mastering, so I kind of forget what happens in it. I learned a lot of what it wasn’t, but I don’t know if I learned what it is. I would rather find the next question than find the answer: that’s just the way I am. I mean, I don’t really believe in answers. A solution should lead to the next question.

I:

A bit like a filmmaker working in a genre, you have a choice: “Am I going to take this convention and play with it or am I going to confound this convention?”

J:

That’s a really apt comparison for me, because those kinds of filmmakers were a much bigger influence on me than music really was when I was young. I always wanted to be a filmmaker and then I found out how expensive it is and what kind of life you have to lead so that didn’t happen. Someone like Robert Aldrich or Richard Fleischer, these kinds of filmmakers were a really big deal for me because I loved watching them do all sorts of things despite being in this supposed cage of genre convention. William Friedkin is like a superhero to me: I love William Friedkin. To Live and Die in L.A., that film is amazing in what it does with genre conventions. I have a huge poster of it staring in my face right now. My way of thinking on that stuff really comes more from film than anything else. Just it really taught me a lot about approach.

I:

I wonder as well if, compared to pop music where the story is told in a very concise nugget, ambient music, where a single piece might be stretched over an entire album, works in a more cinematic rhythm.

J:

Well, in terms of structure, the one thing that music can’t really do eloquently, like the other art forms, is deal with time backwards. Music can really only change time by making reference, and that can only be done if the music has a formal structure because you’re making structural reference or a melodic reference. And that’s really only calling back, that’s not restructuring time. Kurosawa Kiyoshi, in the ‘90s, was the king of that. He deals with time in his films in the most extraordinary manner, especially Hebi no Michi (Serpent’s Path) and Kumo no Hitomi (Eyes of the Spider). The way he restructures everything you’ve seen with just an image, and your perception of time in everything you’ve seen can change from just an image. You can do that in all the visual arts, and obviously you can do that in writing, but music doesn’t have the tools to do that in such an eloquent manner. It’s really kind of clumsy. That’s something that’s always fascinated me since college, because when I was in college and studying all the Stockhausen and all that shit, that was the stuff I was really interested in. There’s this whole period of Stockhausen doing these “moment works”. I mean, the 60s and 70s was when all those guys were trying to address the problem of time in music, and the fact that they did is awesome, but it was really kinda hamfisted. It’s still a problem in music and that’s the thing I think about a lot, and film is the thing that reminds me of that constantly, more so than music does.

I:

You’ve mentioned before constantly creating roadblocks for yourself in the creation of your music.

J:

I don’t think I do that as much as I used to. When I was younger I think I needed to. I think now I sort of trip myself up naturally. I don’t even consciously do that: its just the way my brain works. I think when I was younger I had to do that. And also, when you’re younger, when you have no gear or anything, that’s a great thing, you know? Having too much gear is one of the worst things in the world. The more gear you have, the less you do. That’s a concrete restriction that you’ve got to think about, “I’m not even gonna touch any of that stuff”. There’s only three instruments on this record – no, four, sorry, if you count a short-wave radio as an instrument.

I:

Were you working with any collaborators on this record or is it all you?

J:

Yeah, it’s just me. There was one version that was going to have drums on it but it didn’t work. So there’s a hard-drive full of this stuff with drums on it that will rust away (laughs).

I:

You’re living in the countryside now. Since moving there has that impacted the way you work.

J:

I just get to work more. There’s not much distraction at all. It’s the closest to when I was in my early twenties, really. I mean, I wouldn’t sleep for days at a time: I’d really be in my room with my tape machine and just doing that non-stop. That’s not something I’d want to do now, but I can get to that frame of mind again, which is something I haven’t been able to do for a long long time.

I:

You produce a wide range of music under the name of “Jim O’Rourke”, but there’s often this sense, particularly in Japan, that “this is what this project is and this is what it sounds like”. I remember a friend of mine was playing a show and at the end the manager of the venue commented, “Yeah, that should be three different bands, what you played there”

J:

Yeah, that’s a very reductive way of thinking. I think it is more common here than anywhere else.

I:

You’ve spoken in the past that people have a hard time considering an artist’s work as a whole rather than each thing discretely.

J:

Right, I think that’s more common in music. I mean, you say “Hitchcock “ – people might mention a film or two as their favourites but they’re generally thinking “the work of Hitchcock”. But it is true in music; you would think of “the works of Morton Feldman” but that’s because that world of music does tie into that socio-political way of thinking. But in terms of popular music that really has more to do with commodity than a way of thinking, there really aren’t that many people who approach it that way. Whether you like him or not, Frank Zappa is someone who could be seen as an exception to that: people generally think of “the work of Frank Zappa”, although he was generally making records with a rock band. People think that way about someone like Bob Dylan. So there are exceptions, but in general there aren’t.

I:

Do you feel there are themes that keep coming back in your music?

J:

Oh God, yeah! (Laughs) It’s all the same thing. They’re all the same thing really. I mean, I think it’s something Picasso said or someone said it about Picasso: “You’re really just making the same painting over and over again.”

One silly example, I remember when I was younger, I would read Naked Lunch every year, and I noticed that every year I re-read it, I learned more about me than I did about the book. Because I saw more of how I had changed, in that time, than the book had changed. Because the book, of course, hadn’t changed at all: it’s always been there.

Jim O'Rourke sleep like it’s winter NEWHERE MUSIC |

I: What do you think links an album like Simple Songs to and album like Sleep Like it’s Winter or maybe Kafka’s Ibiki’s Nemutte?

J:

I guess I would say it’s that I made them. (Laughs) It sounds like a joke, but in a way I think that’s really kind of the best answer. Certain aspects of what I’m trying to do come out stronger on some things more than others. But they’re kind of all there on all of them.

I:

One thing that connects them, when I listen to them, is that I hear multiple layers to the way things transition on your records.

J:

I don’t know if you’ve heard this record I did called The Visitor.

I:

Yeah, I was listening to that today, actually.

J:

I mean, that’s probably the closest I’ve ever gotten. It still has lots of problems, but that’s the closest ever to sort of doing what I wish the music would do. And that’s really all about the transitions, really – the flipping and the flopping, as Kramer would say. I don’t think in the abstract about the transitions – I don’t think “OK, now I’m going to make this kind of transition,” – it’s not an abstract idea or an exercise, but that really is a big part of how I put things together. It’s like weaving a rug. I don’t know if that’s an apt analogy, but you don’t want the work put into the music to show. The best rug you ever saw, if you look at the way it’s put together, that work never overshadows the overall effect, hopefully. That’s the hardest thing, I think, in making music - to hide the work. You’ve gotta hide it. That’s really really important to me.

I:

Has that always been a key part of your approach?

J:

It’s always been there. I’m trying to think of where I learned that lesson, but I know I learned it very young. Definitely since like… it was like ’91, ’92 where I got out of the habit of highlighting the work more than what the work was supposed to produce.

That’s kind of part and parcel of how I work. A big percentage of the work is in hiding the work: it needs to live once you’ve killed it, you know what I mean? (Laughs)

I:

Part of the fun of listening to some of your recent records was that on multiple listens, it continues to fundamentally change.

J:

You’ve reminded me. I know I’ve said this before, but this was a big deal for me and it relates 100% to this. When I was in high school there was a movie theatre within like two hundred yards of our house and, because I would go there every day, they eventually just let me go in for free. So I was going there every day. And one day I was going there to go see a movie and my father said, “You saw that movie already, why are you going to see it?” and I remember saying to him, something to the effect of, “All of these people put like a year of their lives into making this movie. How arrogant would it be for me to think I could understand it all in two hours?” That was one of the things I really love about film: that good films didn’t have it all out there on the surface like somebody serving you a whatever course dinner. You had to dig in, and some things don’t work without that resonance, that’s very important, ‘cause time equals resonance, you know? One silly example, I remember when I was younger, I would read Naked Lunch every year, and I noticed that every year I re-read it, I learned more about me than I did about the book. Because I saw more of how I had changed, in that time, than the book had changed. Because the book, of course, hadn’t changed at all: it’s always been there. So that was also kind of a profound thing for me when I was a young ‘un.

I:

Perhaps there’s also this idea of having the space to find you way into something. It took me forever to get into Bowie because at first I thought it was “classic rock”, which just had so much baggage attached to it. But because there were so many entry-points into his work I eventually found one that worked for me.

J:

I can understand that. I had that a few years ago with Keith Jarrett. He was someone I knew I was supposed to like and I should have ‘cause I love ECM –70s ECM, the stuff I grew up on. And of course, he’s like a towering figure in that world and it took a long long time. It’s really only in the past two or three years that I finally cracked the code with him.

I:

I can understand that. I guess the point for me is that there wasn’t a single door. There were multiple doors in and I had to find mine.

J:

Right. Well I think there has to be like one initial door and when you open that door there’s all the other doors. Just like… (Laughs) I immediately thought of Genesis, sorry!

I:

You don’t have to apologize for Genesis!

J:

Oh, I will never apologise for Genesis! You’re never going to find a more hardcore Genesis fan than me – Peter era, of course. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is my favourite album of all time. But, you know, Genesis wasn’t embarrassing when I was growing up.

I:

Maybe “I will never apologise for Genesis!” is a good sentiment to end on. Thanks!

by Ian F. Martin(2018年6月25日)

| 12 |

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

INTERVIEWS

- interview with xiexie - オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- interview with salute - ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる ──サルート、インタヴュー

- interview with bar italia - 謎めいたインディ・バンド、ついにヴェールを脱ぐ ──バー・イタリア、来日特別インタヴュー

- interview with Hiatus Kaiyote (Simon Marvin & Perrin Moss) - ネオ・ソウル・バンド、ハイエイタス・カイヨーテの新たな一面

- interview with John Cale - 新作、図書館、ヴェルヴェッツ、そしてポップとアヴァンギャルドの現在 ──ジョン・ケイル、インタヴュー

- interview with Tourist (William Phillips) - 音楽はぼくにとって現実逃避の手段 ──ツーリストが奏でる夢のようなポップ・エレクトロニカ

- interview with tofubeats - 自分のことはハウスDJだと思っている ──トーフビーツ、インタヴュー

- interview with I.JORDAN - ポスト・パンデミック時代の恍惚 ──7歳でトランスを聴いていたアイ・ジョーダンが完成させたファースト・アルバム

- interview with Anatole Muster - アコーディオンが切り拓くフュージョンの未来 ──アナトール・マスターがルイス・コールも参加したデビュー作について語る

- interview with Yui Togashi (downt) - 心地よい孤独感に満ちたdowntのオルタナティヴ・ロック・サウンド ──ギター/ヴォーカルの富樫ユイを突き動かすものとは

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第3回 『天乃川』とエレクトロニク・ミュージック

- interview with Sofia Kourtesis - ボノボが贈る、濃厚なるエレクトロニック・ダンスの一夜〈Outlier〉 ──目玉のひとりのハウス・プロデューサー、ソフィア・コルテシス来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Lias Saoudi(Fat White Family) - ロックンロールにもはや文化的な生命力はない。中流階級のガキが繰り広げる仮装大会だ。 ——リアス・サウディ(ファット・ホワイト・ファミリー)、インタヴュー

- interview with Shabaka - シャバカ・ハッチングス、フルートと尺八に活路を開く

- interview with Larry Heard - 社会にはつねに問題がある、だから私は音楽に美を吹き込む ——ラリー・ハード、来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回 「ロリー・ギャラガーとレッド・ツェッペリン」そして「錦糸町の実況録音」について

- interview with Mount Kimbie - ロック・バンドになったマウント・キンビーが踏み出す新たな一歩

- interview with Chip Wickham - いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 ──サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with Yo Irie - シンガーソングライター入江陽がいま「恋愛」に注目する理由

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第1回 「エレクトリック・ピュア・ランドと水谷孝」そして「ダムハウス」について

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE