MOST READ

- Beyoncé - Cowboy Carter | ビヨンセ

- The Jesus And Mary Chain - Glasgow Eyes | ジーザス・アンド・メリー・チェイン

- interview with Larry Heard 社会にはつねに問題がある、だから私は音楽に美を吹き込む | ラリー・ハード、来日直前インタヴュー

- Columns 4月のジャズ Jazz in April 2024

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- interview with Shabaka シャバカ・ハッチングス、フルートと尺八に活路を開く

- Columns ♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く

- claire rousay ──近年のアンビエントにおける注目株のひとり、クレア・ラウジーの新作は〈スリル・ジョッキー〉から

- interview with Keiji Haino 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回

- Larry Heard ——シカゴ・ディープ・ハウスの伝説、ラリー・ハード13年ぶりに来日

- 壊れかけのテープレコーダーズ - 楽園から遠く離れて | HALF-BROKEN TAPERECORDS

- Bingo Fury - Bats Feet For A Widow | ビンゴ・フューリー

- 『ファルコン・レイク』 -

- レア盤落札・情報

- Jeff Mills × Jun Togawa ──ジェフ・ミルズと戸川純によるコラボ曲がリリース

- 『成功したオタク』 -

- まだ名前のない、日本のポスト・クラウド・ラップの現在地 -

- Free Soul ──コンピ・シリーズ30周年を記念し30種類のTシャツが発売

- CAN ——お次はバンドの後期、1977年のライヴをパッケージ!

- Columns 3月のジャズ Jazz in March 2024

Home > Interviews > interview with Dry Cleaning - 壊れたるもののテクスチャー

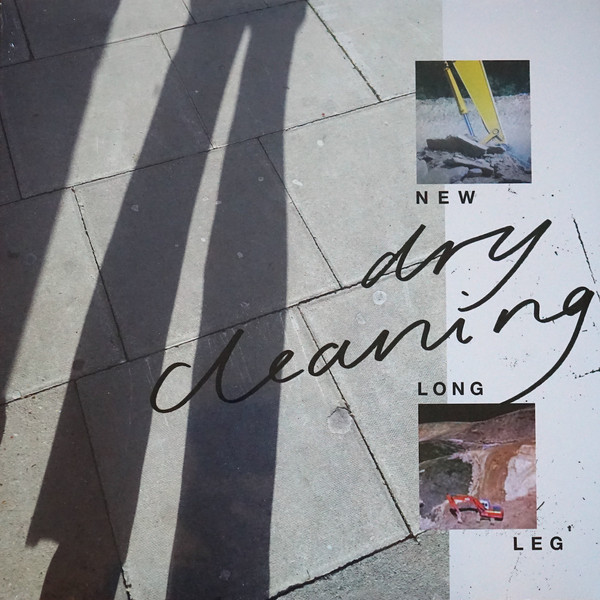

interview with Dry Cleaning

壊れたるもののテクスチャー

——ドライ・クリーニング、インタヴュー

The texture of broken things

by Ian F. Martin

Stumpwork is a funny word. It feels funny in your mouth, and it only gets more awkward once you start breaking it down to untangle its meaning. A stump is a broken or incomplete thing — the remains of a dead tree or the place where an amputated limb used to attach — and it seems like a strange thing to dedicate one’s labour toward.

It refers to a form of embroidery where threads or other materials are layered to create an embossed, textured pattern, giving a feeling of three dimensional depth to the image, and perhaps in this we can reach out and contrive a connection with the increasingly rich and intricately textured music of Dry Cleaning. But we shouldn’t forget that it’s first and foremost a viscerally strange and funny word.

Florence Shaw is one of the most interesting lyricists in the English language right now, and she has a remarkable instinct for interesting and evocative phrasing. Just as with the title itself, she seems to take a sort of joy in the inherent sonic texture of a word — the way she hangs on the hard t and trailing vowels of the word “otters” in the song Kwenchy Kups is both musical and quietly comical. There’s a constant delight in the awkwardness of small errors and unconventional phrasings that reveals itself in words and expressions like “dog sledge”, “shrunking” and “let’s eat pancake” that deviate disconcertingly but never incomprehensibly from linguistic norms. This playful texture is also ever-present in her instinct for juxtaposing the magical and the mundane that results in lines like, “Leaping gazelles and a canister of butane”. Dry Cleaning’s lyrics play out like a story where the connecting tissue of narrative has been stripped out, leaving only the details and colour — a collage of dozens of voices that adds up to an impressionistic emotional tableau.

Musically, Stumpwork reveals a broader, richer palette than the band’s (also excellent) 2021 debut full-length New Long Leg. The band’s sound has often been characterised with the elastic term post-punk, and you can hear elements that recall the choppy angles of Wire or the chiming sounds of Felt and Durutti Column in Tom Dowse’s expressive guitar work, but he takes it further this time, twisting it into queasy, drunken distortions or ambient haze. Bassist Lewis Maynard and drummer Nick Buxton make for a subtle and imaginative rhythm section that brings in ideas and dynamics from beyond punk and indie tradition. Smooth washes of almost city pop synth welcome you into opening track Anna Calls From The Arctic, and unexpected and oblique arrangements pull you gently one way and another throughout the album. It’s not an album possessed of an urgent need to grab your attention so much as a shimmering palette of colours to melt into.

It’s not an as disaffected and worn as ever. Britain’s confused political situation filters through, most explicitly in the song title Conservative Hell, and I catch up with Tom and Lewis in the middle of a particularly chaotic moment. The Queen has just been buried a couple of weeks prior, and the delusional cruelty of prime minister Liz Truss has recently replaced the ramshackle cruelty of Boris Johnson, but not quite yet given way to the vacant, lifeless cruelty of Rishi Sunak.

It’s been three years since I last had a chance to visit the UK, so I open with a big question.

IAN: So what’s it like living in Britain these days?

TOM: If you look at the news, it’s a living nightmare. Beyond that, though, things just carry on kind of as they were before, really. One thing that I think has happened now with the new prime minister is that this is the nadir: this is the endgame of Conservative politics. We’ve had twelve years of austerity and no growth, and even high ranking MPs are sort of admitting that they need to be an opposition party now. So one good thing about that is that the Conservatives are going to get voted out in the next election. The downside is that until that happens, we have to live with the stupid policies they have.

LEWIS:Even someone like my sister, who totally ignores it, even she’s like, “It’s shocking; it’s really fucking expensive!” — the bills, the food shopping, it’s getting really tough now.

T:That’s a really good point. If you want to lose the next election, fuck with people’s mortgages!

I:I’m hearing similar things from my family too, yeah. So seeing if I can segue this into the new album… (everyone laughs) What you were saying earlier about life going on as normal but with little pieces of the situation coming through, it feels like if the political situation in the UK informs the album, it’s in these little fragments filtering through normal life, like at one point Florence just remarks, “Everything’s expensive…”

T:“Nothing works.” Yeah, it’s quite difficult for us to comment on Flo’s lyrics, but she’s definitely the kind of person who wouldn’t make a song about one subject. Her songs remind me of the way your brain works. I remember being hit by a car on my bike once, and on the edge of the void there’s all sorts of strange things that come to your mind. But I should clarify what I said earlier about how everyone’s just getting on with things: everyone’s just getting on with things but under a very oppressive shadow. You still have to go to work, you still have to pay your bills, you still have to do all the normal things, it’s just that the political climate — we’ve been under this for twelve years, and if you’re an even slightly curious or observant person, it’s going to affect you.

L:We write together in the room at the same time, and she’ll have a stack of papers which will have lyrics that she’s written and will sort of combine and join together, and there’s lots of circling that and dragging it to that, making almost a collage where lots of different ideas come together.

I:When I’m listening, it feels like fragments of something flowing past me.

T:It’s not random though. When she writes a line, she has the sort of temperament to write the opposite line next — something completely different tonally, texturally, conceptually. It’s almost like when you’re making a painting or something, you’re trying to balance all the elements so it works nicely.

L:There’s a lot of reacting to us in the room playing our parts and us reacting to her, like a conversation.

I:There’s such an aspect of fragments of daily life to it and I wonder if there’s ever a sense where you’ll be listening to it and think, “Oh, I remember that conversation…”

T:Oh, there’s definitely things that we’ve said or things that friends have said when I was there and they’re in the lyrics.

L:And like ourselves, she improvises a lot when writing her lyrics as well as having some pre-formed ideas. We’ve had to get better at finding ways to record because the room’s quite loud when we’re playing, so a lot of times we’ll separately record the vocals so she can hear back what she said. I think on this record the lyrics changed more when it came to recording than on the first record, but not a huge amount.

T:That was partly because we improvised quite a lot of stuff in the studio. But generally, Flo will start at the same time we start writing the song. We’re all there at the start of it, and like Lewis says, a lot of the time there’s something Flo is doing that informs how we’re doing our thing as well — tonally, if that makes sense. When we were writing Gary Ashby, when I found out she was singing a song about a tortoise that’s gone missing, it changes the way you play; you find ways of punctuating what she’s saying, making it more charming or melancholy, you might use a minor chord or something that you wouldn’t have done before. It’s rare that we’ll write a whole song and then she’ll go away and write all the lyrics — that never happens, and it’s a more organic thing.

L:We’ll react to her in the same way we react to each other. I’ll react to the drums in the same way I react to the drums and the guitar, and vice versa. It’s another instrument in the room.

I:How has the approach changed, since the early EPs and the last album in particular?

T:We still write in the same way. We write by basically just jamming together.

L:There’s a lot of phone demos. We’ll be having a jam, think “This sounds OK” and someone just clicks on their phone and starts recording, and then sometimes we’ll work on it the next week or sometimes it’ll get lost for six months and someone will be like, “Hey, that jam from six months ago was quite good.” That’s how almost everything starts. This time, because we had more time in the studio, we intentionally went in with ideas less finished.

T:Yeah, the change in approach was basically that we got more time. Before we had two weeks to get it down as quickly as possible.

L:Also, with the first record, we were doing some tours beforehand, so we were playing some of that record live before we recorded it. This time we didn’t get a chance to do that: we recorded it and now we’re in the process of learning it.

I:Right, and I was wondering how not having the constant physical presence of the audience while you were developing the songs affected the process on this one.

T: It’s hard to say really, because without actually road testing the song, you never know. We just embraced it really: we couldn’t play live, so we just write the album the way we wanted to.

L:It comes down to listening, because things get captured differently in the studio as well. It’s quite nice to be able to try something in the studio and a lot of our writing process comes down to listening — like listening back to jams. It’s a nice way of doing it, because if we weren’t recording and listening back and editing from there, a lot of our songs would be based on what was the most fun to play, but that rarely happens because it’s all about listening. And I think that happens as well with not being able to play it live: it’s less about what’s fun to play and more about what sounds good.

T:I think also we learned from the first record that just because you’ve recorded a song one way, that’s not necessarily how it has to be live again, so that’s why we’re sort of relearning the album now. There’s things on the album that definitely need to be on there, but there’s also things that we can just make up again.Touring New Long Leg, there’s Her Hippo and More Big Birds where they just changed and became slightly different songs — added a new part to them, made them longer.

L:Sometimes by accident as well. Sometimes they kind of naturally evolve through a tour.

I:One thing that happens a few times on the new album is that a song will work its way to a natural sounding conclusion, I’ll think it’s ended, but then it will come back and sometimes as something quite different from what it was before. Was that something that came out of having more time to play around in the studio?

T:I think there’s several factors there. First, when we did Every Day Carry, that was the first time we did that in the studio, literally making three parts and kind of improvising some of them. When we did Conservative Hell, that whole last section of that song really came from the first part of the song down and feeling like there was something missing, and John (Parish, producer) was very good at motivating us to just go and make something up.

L:On the first album, John was quite good at making songs snappy, but with Every Day Carry we sort of extended it — and I think he quite enjoyed that process. When it came to the second album, we were kind of prepared for him to make things shorter again, but he seemed to extend stuff more. i think he kind of enjoys it, like, “It’s good when it’s longer!” He surprised us quite a lot by extending songs.

I:That’s John Parish, your producer, right?

L:Yeah.

I:He’s from around my hometown in Bristol. He produced one of my favourite albums, Joy Ride by The Brilliant Corners… (everyone laughs) I know he’s done way more famous albums than that, but they’re one of my favourite bands!

T:That’s one of the great things about John: he’s not the kind of person to brag about things or he doesn’t namedrop much, but when you’re having dinner, he’ll say something — he told me he did a Tracy Chapman record, and I was like, “What!?” He’ll have these stories, but you have to get it out of him naturally.

I:Was it more relaxing working with him this second time, with the familiarity?

T:I think in several ways. Firstly, we were more comfortable, just in ourselves; we’d been doing it longer and had more confidence. The fact New Long Leg did well gave us confidence, we’d played bigger shows by that point, and we were just feeling comfortable. I remember doing takes on the first record and feeling, “This has to be amazing, I have to give this everything!” and then you realise you don’t. Making an album is so complicated, there’s so many layers to it that by the time it’s mixed and mastered, you’ve completely forgotten what it was you were trying to do. So definitely on this one we sort of accepted things the way they were; you try to get a good take, if John’s happy, you move on to the next thing.

L:With the first one as well, we recorded it so quickly with John. We met him and within a few hours, we’d tracked Unsmart Lady, then we moved on to the next one and moved on to the next one. We didn’t have time to play so much.

T:Yeah. And it was a bit of a shock to the system last time when he would say things like, “I don’t like that. Change it.” (laughs)

L:And you’d be like, “Uh… now?” We had one day off last time, on the Sunday, and on Saturday, he was like, “I don’t like that. Change that tomorrow on your day off. See you Monday!”

T:But by the time we got to the end of that session, we were really onboard with it. We liked the way he worked and you just don’t take it personally. Because you’re more confident, a bit more robust, you can deal with it a bit better — you expect it and you welcome it. So with the second record, if he says to go and do something differently, that’s what you’re looking for.

L:And we’d go into the studio looking for things to change. With the first record, we’d been playing a lot of those songs live, so maybe people were a bit more fixed on their parts and their ideas, so that’s harder to change. This one was a bit more open to change.

I:The sonic texture of this album feels a lot broader than the first one. Did that come naturally, or was there some sort of conscious element to expanding the sound?

T:I think it’s natural in the sense that our listening tastes are so broad. I often feel that if I had more time, I’d do some kind of ambient project, or me and Lewis could do a metal band together. For sure Nick would do some kind of dance music, wouldn’t he?

L:And Dry Cleaning’s a nice collaboration of all those ideas pulling nicely in different directions.

T:The way Lewis described the transition from the first record to this one, it’s like the first record left little markers down for different directions to go in and on the second record we take them all a little bit further. And then hopefully on the third one if we get the opportunity to do another one, we’ll take it even further. It’s all about exploring different avenues. So when things seem to go a little more ambient, we’re already into that kind of music and we’ll go with it as opposed to being sort of, “Oh, I don’t want to make that kind of music.”

L:We’re learning more about what we can do in the studio as well. The first EP was really like a demo, recorded in a couple of hours. You don’t get much time to play in the studio, so you sort of write your parts for what sounds good in the rehearsal room. Writing the second record, we were writing for the studio more. We’d be writing a song and Tom would go, “There should be a twelve string on top of this!” There’d be a keyboard part here, or Nick would be playing really quietly and saying “On the record it’s going to be really big but it just sounds good the way I’m hitting it like this.” You get to experiment more like that.

I:I suppose it’s on Liberty Log where that almost ambient feeling is most pronounced, and I was wondering if writing for what’s mostly spoken word lends itself to a different way of structuring music compared to the traditional pop song structure of verse-chorus-verse-chorus.

L:There were a lot of times where one of us would say, “Should we do the chorus now?” and then we’d be like, “Which one’s the chorus?”

T:Yeah, “What’s the chorus?”

L:And we’d all have to agree on what’s the chorus.

T:Which I think was a good sign, actually. It shows how we’re all thinking in different ways but music is getting done. I think I agree: Lewis has said before in other interviews that one of the strengths of our identity is you have Flo in the middle of everything, and her voice anchors you, and certainly as a musician it feels that you’re given a lot of room to chuck things in. When we first started writing Hot Penny Day, initially when I wrote the main riff it sounded like Goats Head Soup-era The Rolling Stones to me…

L:And then someone fucked it up!

T:And then when I showed it to Lewis and we started playing it together, it started turning into something more like Sleep or stoner rock — made it more groovy.

L:And then Flo gets involved and it instantly sounds like Dry Cleaning. I think her voice and her delivery gives us a lot of scope.

T:I mean, as musicians, having worked with these guys for five years, I think we all have our own sonic motifs — I can tell it’s Lewis, I can tell it’s Nick, they can tell it’s me — but Flo definitely anchors things in Dry Cleaning world.

I:I was angles.

T:I’m really glad you checked our previous bands! I think if you want to understand Dry Cleaning, it has roots in what we’ve done in the past. Like you say, because we’ve got broad music taste, my first experiences in music were in punk and hardcore bands but I did find them stylistically quite limiting. I like the catharsis of fast music, but I also like the melody of REM. I remember seeing La Shark a few times and it was clearly a sort of skewed pop band but their later stuff sounded like instrumental Funkadelic, so it’s almost like there isn’t enough time to put all your influences into one band.

L:I’ll be driving and have little fantasies about combining two bands, and then I’ll meet up with Tom or Nick or Flo and I’ll say that, and they’ll be like, “We should do that!” And once again, it’s still Dry Cleaning. If you took Flo’s vocals off the new album, there’s so many different genres you could put stuff into.

I:You say Florence is in the centre of it all, holding the identity of the band together, but at the same time, she’s also a little bit separate from it in some ways. On the new album, even more than before, the way it’s mixed you hear the band playing, who sound like they’re in a room somewhere, but then her vocals come in and it’s like she’s right up against your ear. Like you’re watching a band on the stage and there’s just this woman whispering in your ear!

L:That reminds me of Flo’s story about her joining the band started with you playing the band and her talking over the top of it.

T:We’d studied visual art together — we were both making comics at the time, and we met up to talk about that. She asked, “What else have you been up to?” and I said, “I’ve started jamming with Lewis and Nick.” I had some demos and she listened to it. Then she took her earphones out, said, “Oh, that’s interesting,” and started talking, and I could hear the music still with her voice over the sound out of the earphones in the background. I think John’s key interest in our band is how he mixes Flo. On this record to a much greater extent you can hear bits of her breath. Flo is a very nuanced performer: just the little things she does, like the click of her tongue or something — very small sonic things that he’s very keen to make sure are in there. I’ve seen him talking about this in an interview, about how you have to hear everything she’s doing: that’s the first thing, and then around that, he builds the mix and brings the band in.

L:She’s always in the room when we’re recording, and she’s tracking at the same time. We’re lucky enough to have isolated rooms, so my amps can be in one room, Tom’s amps can be in another room, Nick could be behind some glass, Flo’s in the room with us, and she keeps a lot of those vocals. There’s a lot of effort put into isolating her vocals so there’s not too much bleed from the band. I agree with what Tom said, John puts a lot of focus on that.

序文と取材:イアン・F・マーティン(2022年11月15日)

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

INTERVIEWS

- interview with Lias Saoudi(Fat White Family) - ロックンロールにもはや文化的な生命力はない。中流階級のガキが繰り広げる仮装大会だ。 ——リアス・サウディ(ファット・ホワイト・ファミリー)、インタヴュー

- interview with Shabaka - シャバカ・ハッチングス、フルートと尺八に活路を開く

- interview with Larry Heard - 社会にはつねに問題がある、だから私は音楽に美を吹き込む ——ラリー・ハード、来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回 「ロリー・ギャラガーとレッド・ツェッペリン」そして「錦糸町の実況録音」について

- interview with Mount Kimbie - ロック・バンドになったマウント・キンビーが踏み出す新たな一歩

- interview with Chip Wickham - いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 ──サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with Yo Irie - シンガーソングライター入江陽がいま「恋愛」に注目する理由

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第1回 「エレクトリック・ピュア・ランドと水谷孝」そして「ダムハウス」について

- exclusive JEFF MILLS ✖︎ JUN TOGAWA - 「スパイラルというものに僕は関心があるんです。地球が回っているように、太陽系も回っているし、銀河系も回っているし……」 対談:ジェフ・ミルズ ✖︎ 戸川純「THE TRIP -Enter The Black Hole- 」

- interview with Julia_Holter - 私は人間を信じているし、様々な音楽に耳を傾ける潜在能力を持っていると信じている ——ジュリア・ホルター、インタヴュー

- interview with Mahito the People - 西日本アウトサイド・ファンタジー ──初監督映画『i ai』を完成させたマヒトゥ・ザ・ピーポー、大いに語る

- interview with Tei Tei & Arow - 松島、パーティしようぜ ──TEI TEI(電気菩薩)×AROW亜浪(CCCOLECTIVE)×NordOst(松島広人)座談会

- interview with Kode9 - 〈ハイパーダブ〉20周年 ──主宰者コード9が語る、レーベルのこれまでとこれから

- interview with Zaine Griff - ユキヒロとリューイチ、そしてYMOへの敬意をこめてレコーディングした ──ザイン・グリフが紡ぐ新しい “ニュー・ロマンティックス”

- interview with Danny Brown - だから、自分としてはヘンじゃないものを作ろうとするんだけど……周りは「いやー、やっぱ妙だよ」って反応で ──〈Warp〉初のデトロイトのラッパー、ダニー・ブラウン

- interview with Meitei(Daisuke Fujita) - 奇妙な日本 ——冥丁(藤田大輔)、インタヴュー

- interview with Lucy Railton - ルーシー・レイルトンの「聴こえない音」について渡邊琢磨が訊く

- interview with Waajeed - デトロイト・ハイテック・ジャズの思い出 ──元スラム・ヴィレッジのプロデューサー、ワジード来日インタヴュー

- interview with Kazufumi Kodama - どうしようもない「悲しみ」というものが、ずっとあるんですよ ──こだま和文、『COVER曲集 ♪ともしび♪』について語る

- interview with Shinya Tsukamoto - 「戦争が終わっても、ぜんぜん戦争は終わってないと思っていた人たちがたくさんいたことがわかったんですね」 ──新作『ほかげ』をめぐる、塚本晋也インタヴュー

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE